摘 要: 早产儿喂养不耐受是目前新生儿最常见的临床问题之一,常导致达全肠内营养时间延迟,住院时间延长。防治早产儿喂养不耐受对提高早产儿存活率有重要意义。该指南基于目前国内外研究,采用证据推荐分级的评估、制定与评价方法(GRADE)进行证据分级制定早产儿喂养不耐受的临床诊疗指南,旨在帮助新生儿科医生、护理人员、营养治疗师等对早产儿喂养不耐受进行早期识别与规范管理。

关键词: 喂养不耐受; 指南; 低出生体重儿; 早产儿;

Abstract: Feeding intolerance(FI) is one of the most common clinical problems in preterm infant and often leads to the delay in reaching total enteral nutrition and prolonged hospital stay. The prevention and treatment of FI are of great significance in improving the survival rate of preterm infants. With reference to current evidence in China and overseas, the clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of FI in preterm infants were developed based on Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation(GRADE), so as to help neonatal pediatricians, nursing staff, and nutritionists with early identification and standard management of FI in preterm infants.

Keyword: Feeding intolerance; Guideline; Low birth weight infant; Preterm infant;

早产儿喂养不耐受(feeding intolerance,FI)是指在肠内喂养后出现奶汁消化障碍,导致腹胀、呕吐、胃潴留等情况。FI病因不清,可能与早产致肠道发育不成熟有关,也可能是坏死性小肠结肠炎(necrotizing enterocolitis,NEC)或败血症等严重疾病的早期临床表现[1],常发生于胎龄小于32周或出生体重小于1 500 g的早产儿。FI一旦发生,常导致营养不良、生长受限,并致达全肠内营养时间延迟,住院时间延长,严重威胁早产儿生存。因此,及时发现FI,早期有效、安全干预十分必要。本指南基于循证证据制定早产儿FI临床诊疗方案以促进对FI的规范管理。

本指南(国际实践指南注册号:IPGRP-2020CN057)目标人群为新生儿科医生、护理人员和营养治疗师等,适用人群为早产儿或低出生体重儿。

本指南采用对象-干预-对照-结局(participants-interventions-comparisons-outcomes,PICO)法提出临床问题。(1)对象:喂养不耐受早产儿;(2)干预措施:如药物干预、不同乳制品及喂养方式干预等;(3)对照:安慰剂;(4)结局:主要结局包括腹胀、呕吐等发生率或达全肠内营养的时间,次要结局为不良反应发生率,如NEC、病死率等。检索文献库包括PubMed、Embase、Cochrane Library、Web of Science、中国知网、维普及万方数据等数据库,检索时间均为建库起至2020年8月20日。

本指南证据和推荐级别依照证据推荐分级的评估、制定与评价方法(Grading of Recommenda-tions Assessment,Development and Evaluation,GRADE)[2]。证据级别分为高、中、低和极低4级(表1)。推荐强度分为强推荐和弱推荐:强推荐指当干预措施明确显示利大于弊或弊大于利时所作推荐;弱推荐指当利弊不确定或无论质量高低的证据均显示利弊相当时所作推荐。

表1 GRADE证据等级及推荐强度分级[2]

![表1 GRADE证据等级及推荐强度分级[2]](http://www.xueshut.com/uploads/allimg/200925/36-200925105TY22.jpg)

1 、早产儿FI诊断标准

FI通常是通过胃残余量、腹胀及呕吐或喂养的结局指标进行评价,至今FI尚无国际统一的诊断标准。

推荐意见1:以下2条推荐意见符合1条则可诊断为FI。

(1)胃残余量超过前一次喂养量的50%,伴有呕吐和/或腹胀(B级证据,强推荐)。

(2)喂养计划失败,包括减少、延迟或中断肠内喂养(B级证据,强推荐)。

推荐意见2:不推荐通过测量腹围或观察胃残余物的颜色诊断FI(C级证据,弱推荐)。

推荐说明:胃残余量升高提示胃排空不良及胃肠动力减退。有研究认为FI应具备以下三者之一:(1)单次胃残余量大于前次喂养量的50%;(2)至少两次胃残余量大于前次喂养量的30%;(3)胃残余量大于每日总喂养量的10%[3]。美国儿科学会(American Academy of Pediatrics,AAP)定义FI为胃残余量≥2~3次喂养总量的25%~50%[4]。科学家们用概念分析法研究后认为最适合临床的FI定义为单次胃残余量大于前次喂养量的50%[5]。

因腹胀、大便性状及排便方式均对FI有一定影响,故胃残余量不能单独作为FI的诊断标准。一些研究中将FI定义为胃残余量升高,可能伴腹胀或呕吐等临床表现[3,6]。目前大多数研究倾向于将腹胀或呕吐或两者均存在作为FI的重要指标之一。故Moore等[5]通过概念分析法建议将FI定义为:胃残余量超过前一次喂养量的50%,伴有呕吐和/或腹胀。

2015年加拿大制定的《极低出生体重儿喂养指南》提出,全肠内营养的目标为体重<1 000 g及<1 500 g的早产儿分别在开始肠内喂养后2周及1周内达到150~180 mL/(kg·d)[7]。喂养计划失败主要指在指定时间内未达全肠内营养,喂养过程中因FI出现而减少喂养次数或中断喂养等。因通过喂养计划更易量化判断是否存在FI,故一些研究将达全肠内营养的时间或在肠内营养过程中,需要中断肠内营养并添加肠外营养作为FI的评价标准[8,9,10,11]。

一项多中心随机研究认为,早产儿胃残余物的颜色并不能提示FI[12]。2015年加拿大制定的《极低出生体重儿喂养指南》指出,单纯黄色或绿色胃残余物颜色不能作为FI诊断的参考,同时提出不推荐使用腹围测量值诊断FI[7]。

2 、预防或治疗早产儿FI喂养乳品的选择

推荐意见1:推荐首选亲母母乳喂养(B级证据,强推荐)。

推荐意见2:在亲母母乳不足或缺乏情况下,推荐使用捐赠人乳替代(B级证据,强推荐)。

推荐意见3:在亲母母乳或捐赠人乳不足或缺乏情况下,推荐使用早产儿配方奶(C级证据,强推荐)。

推荐意见4:不推荐常规使用水解蛋白或氨基酸配方奶,仅对极重度FI时可考虑使用(B级证据,弱推荐)。

推荐意见5:不推荐常规使用低乳糖配方奶或乳糖酶(C级证据,弱推荐)。

推荐说明:AAP及世界卫生组织(World Health Organization,WHO)均推荐早产儿首选亲母母乳喂养[13,14]。一项前瞻性队列研究认为,亲母母乳喂养发生FI的概率较捐赠人乳低,中断喂养的比例也明显降低[15]。相比配方奶及混合喂养,纯母乳喂养可缩短达全肠内营养时间、降低FI发生率[16]。相比配方奶,纯母乳喂养可降低NEC发生率[17]。一项成本效益分析研究表明,纯母乳喂养可缩短住院时间,降低经济成本[18]。

关于早产儿喂养,AAP和WHO均提出,在早产儿无法获得母乳的情况下,可使用捐赠人乳替代[13,14]。一项对比捐赠人乳及早产儿配方奶对FI影响的Cochrane系统评价结果显示,捐赠人乳发生FI的风险与早产儿配方奶无明显差异,但NEC发生率低[11]。

在无法获得人乳的情况下,推荐使用早产儿配方奶,包括液态及粉状两种。一项RCT研究发现,液态配方奶喂养的早产儿较奶粉喂养的早产儿发生FI的比例明显增高[19]。但目前关于液态及粉状配方奶与FI的研究证据较少,尚不能系统评价两者在降低早产儿FI中的优劣。

一项Cochrane系统评价比较了水解蛋白配方奶(部分及完全水解蛋白配方奶)及标准配方奶喂养时FI的发生率,发现水解蛋白配方奶并未降低FI发生率及NEC发生率,且相比早产儿配方奶,水解蛋白配方奶喂养的早产儿体重增长速度减慢[20]。也有研究显示,使用水解蛋白配方奶喂养的早产儿较标准配方喂养的早产儿达全肠内营养时间早,FI发生率下降[21,22]。

氨基酸配方奶是一种特殊的配方奶,常用于对牛奶蛋白过敏的患儿。研究认为,早产儿出现严重FI时,使用氨基酸配方奶可明显减少胃残余量[23]。使用氨基酸配方奶喂养的早产儿,粪便中钙卫蛋白含量下降,提示氨基酸配方奶可能通过降低钙卫蛋白的致炎作用而降低肠道炎症,改善FI[24]。因此认为使用氨基酸配方奶对严重FI有效。

有研究认为,低乳糖配方奶可降低胃残余量和中断喂养次数,但研究证据较少[25]。一项Cochrane系统评价认为,目前证据尚不足以支持低乳糖配方奶或乳糖酶用于防治FI,故暂不推荐[26]。

3、 母乳强化剂的使用与早产儿FI

推荐意见1:推荐按个体化原则添加母乳强化剂(human milk fortifier,HMF)(C级证据,强推荐)。

推荐意见2:推荐选择牛乳或人乳来源的HMF(B级证据,强推荐)。

推荐意见3:推荐选择水解或非水解蛋白的HMF(C级证据,强推荐)。

推荐意见4:推荐选择粉状或液态HMF(C级证据,强推荐)。

推荐说明:出生体重小于1 800 g的早产儿在母乳喂养量达50~80 mL/(kg·d)时,应开始在母乳中加入HMF[27]。一项前瞻性研究发现,纯母乳喂养、半强化母乳喂养及足量强化母乳喂养对早产儿的胃排空时间无影响[28]。我国“母乳强化剂应用研究协作组”研究发现,添加HMF不会增加FI的风险[29]。一项Cochrane系统评价也提出,HMF不会增加发生NEC的风险[30]。

HMF来源有3种:人乳、牛乳及其他乳制品。有研究发现,使用人乳和牛乳来源的HMF,二者发生早产儿FI的差异无统计学意义[31,32],且NEC发生率的差异也无统计学意义[17,31,32]。有研究认为,使用驴乳来源的HMF,早产儿FI发生率比牛乳来源的HMF低[33]。但该研究样本量较小,目前对驴乳来源HMF的研究报道也少,故未作推荐。目前国内尚无人乳来源的HMF,故推荐根据可获得性选择牛乳或人乳来源的HMF。

近年国外研究认为水解或非水解蛋白HMF喂养的耐受性均较好[34]。2019年我国《早产儿母乳强化剂使用专家共识》也提出,需要使用HMF时,水解或非水解蛋白配方均可选择[27]。对粉状或液态HMF的选择,研究认为,二者达全肠内营养时间无明显差异,提示两种HMF均可作为推荐[35]。

4、 喂养方式与早产儿FI

推荐意见1:推荐早期微量喂养(B级证据,弱推荐)。

推荐意见2:推荐间断性喂养,如不耐受则选择持续性喂养(B级证据,强推荐)。

推荐意见3:推荐按个体化原则进行喂养加量,快速加量喂养不能降低FI(B级证据,弱推荐)。

推荐意见4:推荐使用初乳口腔免疫法(B级证据,强推荐)。

推荐意见5:不推荐常规使用经幽门喂养(B级证据,强推荐)。

推荐说明:2013年《中国新生儿营养支持临床应用指南》[36]与2015年加拿大的《极低出生体重儿喂养指南》[7]均建议生后尽快微量喂养,认为其可促进胃肠道的成熟,改善FI。另有研究认为,早期喂养[生后96 h内达24 mL/(kg·d)]不能缩短达全肠内营养时间,不能改善FI,但也不会增加NEC发生率[10]。这提示早期微量喂养改善FI的证据不充分,尚需更大样本的高质量研究提供证据。

间断性喂养通常为每2~3 h喂养10~20 min,持续性喂养通常是通过输液泵持续喂养。有研究显示,两种喂养方式达全肠内营养的时间及发生NEC的风险无差异[37]。但持续性喂养时因营养液流速极慢,可导致脂肪等营养素附着在输液管壁,造成营养成份丢失[38]。故建议在持续性喂养过程中应尽量使营养素不附着管壁。

临床上喂养量增加的速度尚无定论。目前常见的缓慢加量速度为10~20 mL/(kg·d),快速加量速度为20~35 mL/(kg·d)。一项Cochrane系统评价比较了两种加量速度对喂养的影响,结果显示,快速加量可缩短达到全肠内营养时间,且不增加NEC的风险[39]。但该研究未对不同体重的患儿进行分层分析,故证据质量有限。

2009年Rodriguez等[40]首次提出初乳口腔免疫法,即使用初乳进行口咽部的预喂养,在喂养前5 min用无菌注射器在患儿口腔内滴入初乳(一般为0.2 mL),初乳通过口腔黏膜吸收,刺激口咽部相关淋巴组织,可促进早产儿免疫系统成熟。研究发现,相比0.9%氯化钠溶液组,使用初乳口腔免疫法的早产儿,FI发生率明显降低[41,42]。目前初乳口腔免疫法开始的时间、频次及持续时间尚未统一,但均主张早期使用。多选择在生后24 h内进行,每2~4 h次,持续5~7 d,也有研究提出初乳口腔免疫可持续到校正胎龄32周或达全肠内营养[43,44,45]。

经幽门喂养(即将肠饲管放置在十二指肠或空肠进行喂养),理论上可保证奶汁达到营养吸收的主要部位,减少反流。Watson等[46]系统评价了经幽门喂养及胃管喂养是否减少FI,发现二者无差异,但经幽门喂养的胃肠功能紊乱发生率却明显升高。故不推荐常规使用经幽门喂养。

5、 药物预防或治疗早产儿FI

推荐意见1:推荐使用益生菌(B级证据,弱推荐)。

推荐意见2:不推荐常规使用红霉素(B级证据,弱推荐)。

推荐意见3:不推荐使用西沙比利、甲氧氯普胺(B级证据,强推荐)。

推荐意见4:不推荐使用多潘立酮(C级证据,弱推荐)。

推荐意见5:不推荐使用促红细胞生成素(erythropoietin,EPO)(B级证据,弱推荐)。

推荐意见6:不推荐常规使用促进排泄药物,仅在胎便排尽明显延迟时考虑促排泄(B级证据,弱推荐)。

推荐说明:益生菌具有通过多种途径提高肠道成熟度及改善肠道功能的潜能。研究发现,使用益生菌可缩短达全肠内营养时间,且无不良反应[47]。目前研究较多的益生菌有乳酸杆菌、双歧杆菌、鼠李糖乳杆菌、布拉氏酵母菌等,但针对益生菌的剂量、使用起始时间及疗程等尚无定论。故益生菌在临床的使用仍有一些争议,仍需大样本RCT,尤其是在国内进行的研究来进一步论证。

红霉素作为一种胃动素激动剂,可通过刺激胃动素分泌促进胃肠道运动[48]。2015年加拿大的《极低出生体重儿喂养指南》提出,临床使用红霉素仍有争议,尚无足够证据支持使用红霉素可预防或治疗FI[7]。一项Cochrane系统评价也发现,无论大剂量[>12 mg/(kg·d)]或小剂量[3~12 mg/(kg·d)]红霉素用于预防或治疗早产儿FI,都无任何益处[3]。

西沙比利和甲氧氯普胺均为胃肠动力药物。研究发现,西沙比利可降低胃残余量,但不能减少达全肠内营养的时间[49]。有报道认为,西沙比利可导致早产儿心脏不良反应,如QT间期延长等[50]。甲氧氯普胺可促进胃排空,使达全肠内营养时间明显缩短,喂养暂停次数减少[51]。但因甲氧氯普胺是一种多巴胺拮抗剂,部分患儿用后可出现锥体外系不良反应[52]。故不推荐使用西沙比利和甲氧氯普胺。

多潘立酮也是一种促胃肠动力药物。国外研究发现,多潘立酮可促进早产儿胃排空[53]。国内研究也认为多潘立酮可减少早产儿FI发生率[54]。但因目前该药用于早产儿属超说明书用药,其安全性和有效性还需大样本高质量的证据支持,故暂不推荐。

EPO是一种内源性糖蛋白激素,可促进红细胞生成,但有研究显示,当EPO与新生儿肠道的EPO受体结合,可促进肠道细胞迁移,对肠道发育有重要作用[55,56]。但针对EPO治疗或预防FI仍存争议。研究发现,EPO可缩短达全肠内营养的时间,不影响患儿血液中的红细胞生成素及血细胞计数[57]。但最近的研究却认为,EPO不能减少FI、呕吐及中断喂养的发生,且可升高中性粒细胞绝对值计数[58]。故临床暂不推荐使用EPO治疗或预防FI。

肠道阻塞、胎便黏稠度升高会减慢胃肠运动、增加胃潴留等。胎便的正常排尽与肠道功能及FI息息相关[59]。研究显示,发生FI早产儿其胎便排尽时间平均约为生后12 d,比未发生FI者明显延长[60]。目前常用的促排泄方法包括甘油制剂灌肠、0.9%氯化钠溶液灌肠及口服渗透性泄剂(如乳果糖等)。研究发现,预防性使用促排泄药物不能改善达全肠内营养的时间及NEC发生率[61]。有研究认为口服渗透性泄剂有增加NEC的风险[62]。故目前证据不支持常规使用促排泄药物预防或治疗FI。

6 、护理在防治早产儿FI中的实践

推荐意见1:推荐口腔运动干预以改善FI(B级证据,强推荐)。

推荐意见2:推荐袋鼠式护理以改善FI(B级证据,强推荐)。

推荐意见3:推荐辅助腹部按摩以改善FI(B级证据,弱推荐)。

推荐意见4:不推荐喂养后选择最佳体位改善FI(C级证据,弱推荐)。

推荐说明:口腔运动干预包括非营养性吸吮及口腔按摩。非营养性吸吮可增加胃泌素分泌,促进胃肠道运动及黏膜成熟,目前常见的非营养性吸吮主要遵循Beckman创建的口腔运动网[63]。Foster等[64]的系统评价发现,非营养性吸吮可缩短达全肠内营养的时间。口腔按摩可通过被动刺激促进口腔肌肉及相关神经的发育[65,66]。研究发现口腔按摩也可缩短达全肠内营养的时间[67]。故目前提倡联合非营养性吸吮和口腔按摩预防或治疗FI。研究表明,联合以上2种方式进行口腔运动干预的患儿胃潴留、腹胀及呕吐发生的比例明显下降[68]。

袋鼠式护理又称“皮肤接触护理”,即通过母亲与新生儿的肌肤抚触来进行护理。有研究发现,采用袋鼠式护理的患儿达全肠内喂养时间明显缩短[69]。联合采用袋鼠式护理及常规护理比单纯采用常规护理可更加有效降低FI患儿呕吐、腹胀及胃潴留的发生,同时还可降低NEC的发生率[70]。

一项系统评价的结果显示:腹部按摩可显着减少早产儿胃残余量及呕吐次数[71]。推荐腹部按摩频率为2次/d,每次15 min,以顺时针方向轻柔按摩,根据患儿个体情况,按摩总时间为5~14 d[72]。

有研究认为,喂养后采用俯卧位及右侧卧位的胃残余量较仰卧位及左侧卧位少[73,74]。但因早产儿俯卧位可增加婴儿猝死综合征的风险[75],需严密监护,故出院后不推荐早产儿使用俯卧位。另有研究通过24 h监测早产儿胃食管反流情况,发现喂养后早期左侧卧位及晚期仰卧位食道反流最少[76]。2015年加拿大制定的《极低出生体重儿喂养指南》也推荐喂养后置患儿于左侧卧位,30 min后改为仰卧位,头抬高30°以预防胃食管反流,但未提及该体位可降低FI[7]。因目前对喂养后选择何种体位的研究报道不一,故暂不推荐选择喂养后防治FI的最佳体位。更多关于体位的高质量证据是必要的。

7 、小结

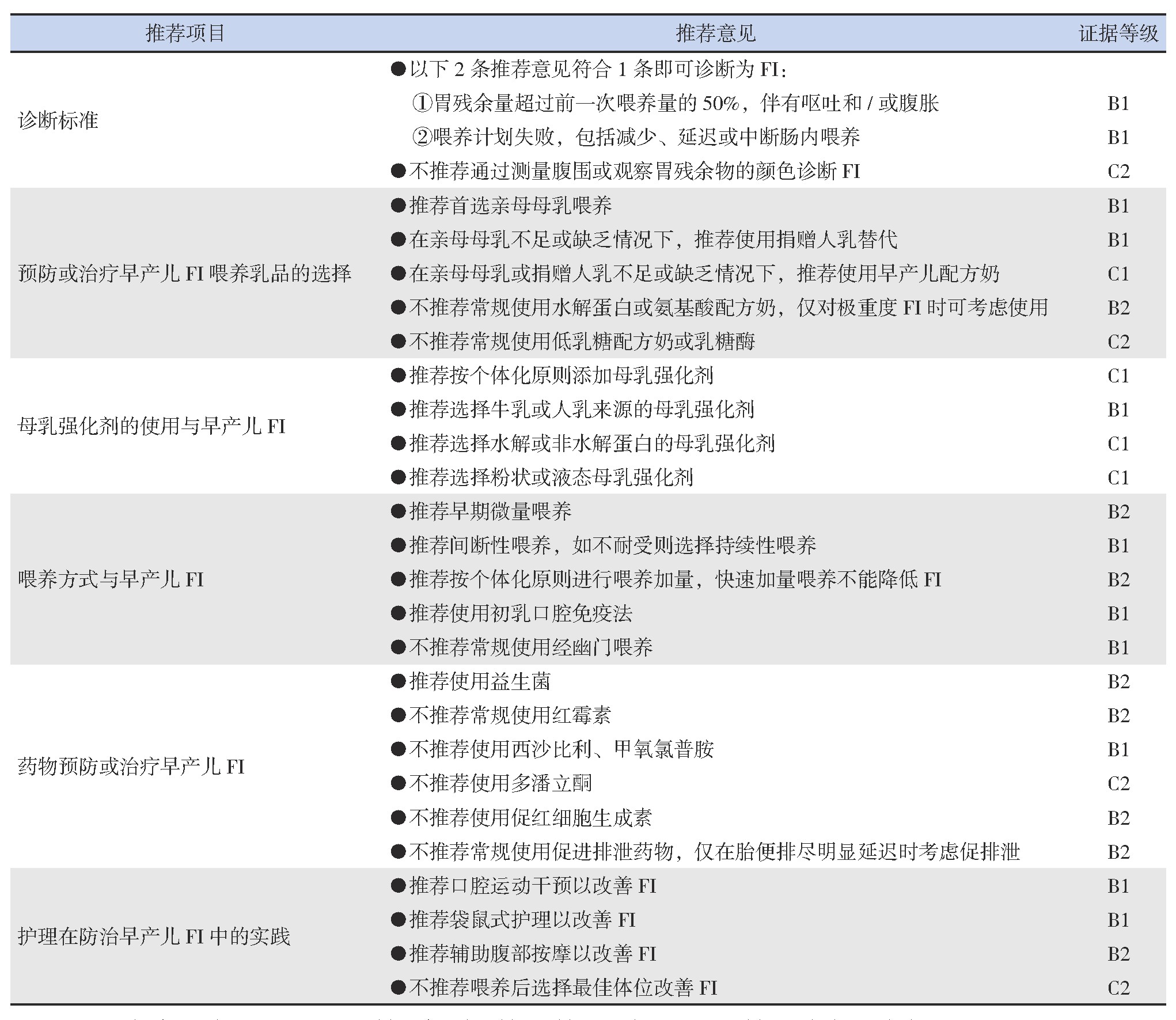

早产儿FI在临床中极为常见,防治早产儿FI是提高早产儿存活率的关键之一。本指南基于目前国内外文献报道,根据GRADE方法进行证据分级,并经同行专家认真讨论后形成。本指南的推荐意见汇总见表2。

表2 早产儿FI临床诊疗指南建议

注:“证据等级”中A、B、C、D分别表示高、中、低、极低质量证据,1、2分别表示强推荐和弱推荐。

参考文献

[1] 唐军.早产儿喂养不耐受:一个重要的临床问题[J].中华围产医学杂志, 2020, 23(3):177-181.

[2] Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA, et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations[J]. BMJ, 2004, 328(7454):1490.

[3] Ng E, Shah VS. Erythromycin for the prevention and treatment of feeding intolerance in preterm infants[J]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2008(3):CD001815.

[4] Kuzma-O'Reilly B, Duenas ML, Greecher C, et al. Evaluation,development, and implementation of potentially better practices in neonatal intensive care nutrition[J]. Pediatrics, 2003, 111(4 Pt2):e461-e470.

[5] Moore TA, Wilson ME. Feeding intolerance:a concept analysis[J]. Adv Neonatal Care, 2011, 11(3):149-154.

[6] Jadcherla SR, Kliegman RM. Studies of feeding intolerance in very low birth weight infants:definition and significance[J].Pediatrics, 2002, 109(3):516-517.

[7] Dutta S, Singh B, Chessell L, et al. Guidelines for feeding very low birth weight infants[J]. Nutrients, 2015, 7(1):423-442.

[8] Costa S, Maggio L, Alighieri G, et al. Tolerance of preterm formula versus pasteurized donor human milk in very preterm infants:a randomized non-inferiority trial[J]. Ital J Pediatr, 2018,44(1):96.

[9] Patole S, Rao S, Doherty D. Erythromycin as a prokinetic agent in preterm neonates:a systematic review[J]. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed, 2005, 90(4):F301-F306.

[10] Morgan J, Bombell S, McGuire W. Early trophic feeding versus enteral fasting for very preterm or very low birth weight infants[J]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2013(3):CD000504.

[11] Quigley M, Embleton ND, McGuire W. Formula versus donor breast milk for feeding preterm or low birth weight infants[J].Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2018, 6(6):CD002971.

[12] Mihatsch WA, von Schoenaich P, Fahnenstich H, et al. The significance of gastric residuals in the early enteral feeding advancement of extremely low birth weight infants[J].Pediatrics, 2002, 109(3):457-459.

[13] American Academy of Pediatrics. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk[J]. Pediatrics, 2012, 129(3):e827-e841.

[14] World Health Organization. Guidelines on optimal feeding of low birth-weight infants in low-and middle-income countries[EB/OL].[2020-08-20]. http://sgk.hztsg.com:8081/rwt/ZGZW/https/P75YPLUYNBYT64LPPE/maternal_child_adolescent/documents/infant_feeding_low_bw/en/.

[15] Ford SL, Lohmann P, Preidis GA, et al. Improved feeding tolerance and growth are linked to increased gut microbial community diversity in very-low-birth-weight infants fed mother's own milk compared with donor breast milk[J]. Am J Clin Nutr, 2019, 109(4):1088-1097.

[16] Assad M, Elliott MJ, Abraham JH. Decreased cost and improved feeding tolerance in VLBW infants fed an exclusive human milk diet[J]. J Perinatol, 2016, 36(3):216-220.

[17] Sullivan S, Schanler RJ, Kim JH, et al. An exclusively human milk-based diet is associated with a lower rate of necrotizing enterocolitis than a diet of human milk and bovine milk-based products[J]. J Pediatr, 2010, 156(4):562-567.e1.

[18] Ganapathy V, Hay JW, Kim JH. Costs of necrotizing enterocolitis and cost-effectiveness of exclusively human milkbased products in feeding extremely premature infants[J].Breastfeed Med, 2012, 7(1):29-37.

[19] Surmeli-Onay O, Korkmaz A, Yigit S, et al. Feeding intolerance in preterm infants fed with powdered or liquid formula:a randomized controlled, double-blind, pilot study[J]. Eur J Pediatr, 2013, 172(4):529-536.

[20] Ng DHC, Klassen JR, Embleton ND, et al. Protein hydrolysate versus standard formula for preterm infants[J]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2019, 7(7):CD012412.

[21] 刘瑶,晁爽,曾超美,等.深度水解蛋白配方在早产儿早期喂养中的疗效观察[J].中国新生儿科杂志, 2012, 27(2):86-90.

[22] 刘运启,何莉霞,雷月娥,等.深度水解蛋白配方乳对极低出生体质量儿早期胃肠功能影响[J].中国社区医师(医学专业), 2013, 15(9):206.

[23] Raimondi F, Spera AM, Sellitto M, et al. Amino acid-based formula as a rescue strategy in feeding very-low-birth-weight infants with intrauterine growth restriction[J]. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr, 2012, 54(5):608-612.

[24] Jang HJ, Park JH, Kim CS, et al. Amino acid-based formula in premature infants with feeding intolerance:comparison of fecal calprotectin level[J]. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr, 2018,21(3):189-195.

[25] Griffin MP, Hansen JW. Can the elimination of lactose from formula improve feeding tolerance in premature infants?[J]. J Pediatr, 1999, 135(5):587-592.

[26] Tan-Dy CR, Ohlsson A. Lactase treated feeds to promote growth and feeding tolerance in preterm infants[J]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2013, 2013(3):CD004591.

[27] 早产儿母乳强化剂使用专家共识工作组,中华新生儿科杂志编辑委员会.早产儿母乳强化剂使用专家共识[J].中华新生儿科杂志, 2019, 34(5):321-328.

[28] Yigit S, Akgoz A, Memisoglu A, et al. Breast milk fortification:effect on gastric emptying[J]. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med,2008, 21(11):843-846.

[29] 母乳强化剂应用研究协作组.母乳强化剂在早产儿母乳喂养中应用的多中心研究[J].中华儿科杂志, 2012, 50(5):336-342.

[30] Brown JV, Embleton ND, Harding JE, et al. Multi-nutrient fortification of human milk for preterm infants[J]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2016(5):CD000343.

[31] O'Connor DL, Kiss A, Tomlinson C, et al. Nutrient enrichment of human milk with human and bovine milk-based fortifiers for infants born weighing <1250 g:a randomized clinical trial[J].Am J Clin Nutr, 2018, 108(1):108-116.

[32] Eibensteiner F, Auer-Hackenberg L, Jilma B, et al. Growth,feeding tolerance and metabolism in extreme preterm infants under an exclusive human milk diet[J]. Nutrients, 2019, 11(7):1443.

[33] Bertino E, Cavallarin L, Cresi F, et al. A novel donkey milkderived human milk fortifier in feeding preterm infants:a randomized controlled trial[J]. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr,2019, 68(1):116-123.

[34] Kim JH, Chan G, Schanler R, et al. Growth and tolerance of preterm infants fed a new extensively hydrolyzed liquid human milk fortifier[J]. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr, 2015, 61(6):665-671.

[35] Moya F, Sisk PM, Walsh KR, et al. A new liquid human milk fortifier and linear growth in preterm infants[J]. Pediatrics, 2012,130(4):e928-e935.

[36] 蔡威,汤庆娅,王莹,等.中国新生儿营养支持临床应用指南[J].临床儿科杂志, 2013, 31(12):1177-1182.

[37] Premji SS, Chessell L. Continuous nasogastric milk feeding versus intermittent bolus milk feeding for premature infants less than 1500 grams[J]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2011,2011(11):CD001819.

[38] Rogers SP, Hicks PD, Hamzo M, et al. Continuous feedings of fortified human milk Lead to nutrient losses of fat, calcium and phosphorous[J]. Nutrients, 2010, 2(3):230-240.

[39] Kennedy KA, Tyson JE, Chamnanvanakij S. Rapid versus slow rate of advancement of feedings for promoting growth and preventing necrotizing enterocolitis in parenterally fed lowbirth-weight infants[J]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2000(2):CD001241.

[40] Rodriguez NA, Meier PP, Groer MW, et al. Oropharyngeal administration of colostrum to extremely low birth weight infants:theoretical perspectives[J]. J Perinatol, 2009, 29(1):1-7.

[41] 李媛媛,赵旭,历广招,等.应用初乳对早产儿进行口腔护理干预效果的系统评价[J].中华护理杂志, 2019, 54(5):753-759.

[42] 许素环,张巧梅,但鑫,等.口腔免疫疗法对早产儿干预效果的Meta分析[J].中国护理管理, 2018, 18(10):1340-1346.

[43] Abd-Elgawad M, Eldegla H, Khashaba M, et al. Oropharyngeal administration of mother's milk prior to gavage feeding in preterm infants:a pilot randomized control trial[J]. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr, 2020, 44(1):92-104.

[44] Rodriguez NA, Vento M, Claud EC, et al. Oropharyngeal administration of mother's colostrum, health outcomes of premature infants:study protocol for a randomized controlled trial[J]. Trials, 2015, 16:453.

[45] Seigel JK, Smith PB, Ashley PL, et al. Early administration of oropharyngeal colostrum to extremely low birth weight infants[J]. Breastfeed Med, 2013, 8(6):491-495.

[46] Watson J, McGuire W. Transpyloric versus gastric tube feeding for preterm infants[J]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2013,2013(2):CD003487.

[47] Athalye-Jape G, Deshpande G, Rao S, et al. Benefits of probiotics on enteral nutrition in preterm neonates:a systematic review[J]. Am J Clin Nutr, 2014, 100(6):1508-1519.

[48] Peeters T, Matthijs G, Depoortere I, et al. Erythromycin is a motilin receptor agonist[J]. Am J Physiol, 1989, 257(3 Pt 1):G470-G474.

[49] Enriquez A, Bolisetty S, Patole S, et al. Randomised controlled trial of cisapride in feed intolerance in preterm infants[J]. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed, 1998, 79(2):F110-F113.

[50] Ward RM, Lemons JA, Molteni RA. Cisapride:a survey of the frequency of use and adverse events in premature newborns[J].Pediatrics, 1999, 103(2):469-472.

[51] Mussavi M, Asadollahi K, Abangah G. Effects of metoclopramide on feeding intolerance among preterm neonates; a randomized controlled trial[J]. Iran J Pediatr, 2014,24(5):630-636.

[52] Eras Z, O?uz SS, Dilmen U. Is metoclopramide safe for the premature infant?[J]. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci, 2013,17(12):1655-1657.

[53] Gounaris A, Costalos C, Varchalama E, et al. Gastric emptying of preterm neonates receiving domperidone[J]. Neonatology,2010, 97(1):56-60.

[54] 张成云,李晓艳,安丽花.多潘立酮预防早产儿喂养不耐受疗效观察[J].临床医学, 2009, 29(7):70-71.

[55] Juul SE, Yachnis AT, Christensen RD. Tissue distribution of erythropoietin and erythropoietin receptor in the developing human fetus[J]. Early Hum Dev, 1998, 52(3):235-249.

[56] McPherson RJ, Juul SE. High-dose erythropoietin inhibits apoptosis and stimulates proliferation in neonatal rat intestine[J].Growth Horm IGF Res, 2007, 17(5):424-430.

[57] El-Ganzoury M, Awad H, El-Gammasy T, et al. The impact of enteral granulocyte colony stimulating factor and erythropoietin on feeding tolerance in preterm infants[J]. Haematologica, 2012,1:434.

[58] Omar OM, Massoud MN, Ghazal H, et al. Effect of enteral erythropoietin on feeding-related complications in preterm newborns:a pilot randomized controlled study[J]. Arab J Gastroenterol, 2020, 21(1):37-42.

[59] Meetze WH, Palazzolo VL, Bowling D, et al. Meconium passage in very-low-birth-weight infants[J]. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr, 1993, 17(6):537-540.

[60] 肖东凡,陈蓉,许天兰. 115例胎龄≤32周早产儿喂养不耐受影响因素的病例对照分析[J].贵州医药, 2019, 43(6):926-929.

[61] Anabrees J, Shah VS, AlOsaimi A, et al. Glycerin laxatives for prevention or treatment of feeding intolerance in very low birth weight infants[J]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2015(9):CD010464.

[62] Deshmukh M, Balasubramanian H, Patole S. Meconium evacuation for facilitating feed tolerance in preterm neonates:a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Neonatology, 2016,110(1):55-65.

[63] Beckman Oral Motor. About Beckman oral motor intervention[EB/OL].[2020-08-20]. http://www.beckmanoralmotor.com/about.html.

[64] Foster JP, Psaila K, Patterson T. Non-nutritive sucking for increasing physiologic stability and nutrition in preterm infants[J]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2016, 10(10):CD001071.

[65] Widstr?m AM, Marchini G, Matthiesen AS, et al. Nonnutritive sucking in tube-fed preterm infants:effects on gastric motility and gastric contents of somatostatin[J]. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr, 1988, 7(4):517-523.

[66] 刘晓娜,杜志方,李娜.新生儿口腔运动干预研究现状[J].发育医学电子杂志, 2019, 7(1):60-63.

[67] Greene Z, O'Donnell CP, Walshe M. Oral stimulation for promoting oral feeding in preterm infants[J]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2016, 9(9):CD009720.

[68] 彭东风,仇宁,范莉莉.非营养性吸吮联合口腔按摩刺激对早产儿经口喂养效果的系统评价[J].安徽医学, 2018, 39(11):1363-1366.

[69] 郝莹.袋鼠式护理干预在喂养不耐受早产儿中的应用[J].河南医学研究, 2020, 29(11):2103-2104.

[70] 黄晓睿,向建文,王越.袋鼠式护理防治早产儿喂养不耐受的临床观察[J].国际医药卫生导报, 2018, 24(21):3356-3358

[71] Seiiedi-Biarag L, Mirghafourvand M. The effect of massage on feeding intolerance in preterm infants:a systematic review and meta-analysis study[J]. Ital J Pediatr, 2020, 46(1):52.

[72] Tekgündüz K?, Gürol A, Apay SE, et al. Effect of abdomen massage for prevention of feeding intolerance in preterm infants[J]. Ital J Pediatr, 2014, 40:89.

[73] 金嘉鋆,黄丽萍,曹洁,等.不同体位鼻饲喂养早产儿的安全性比较[J].中国新生儿科杂志, 2013, 28(5):307-311.

[74] Yayan EH, Kucukoglu S, Dag YS, et al. Does the post-feeding position affect gastric residue in preterm infants?[J]. Breastfeed Med, 2018, 13(6):438-443.

[75] American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. The changing concept of sudden infant death syndrome:diagnostic coding shifts, controversies regarding the sleeping environment, and new variables to consider in reducing risk[J]. Pediatrics, 2005, 116(5):1245-1255.

[76] Corvaglia L, Rotatori R, Ferlini M, et al. The effect of body positioning on gastroesophageal reflux in premature infants:evaluation by combined impedance and pH monitoring[J]. J Pediatr, 2007, 151(6):591-596, 561.e1.